- Home

- Rosanne Parry

Written in Stone Page 11

Written in Stone Read online

Page 11

Henry nodded. “They tried to drill south of here once, maybe fifteen years ago. There was an accident and a spill. Every fish in the river died. It’s been more than ten years and they are still dirt-poor down there.”

“We have to do something,” I said, pacing the length of the table and back.

“We did,” Henry said. “Nobody signed a lease for our land. This letter will warn Grandpa’s cousin Solomon Jackson, and then he’ll know not to sign a lease either.”

“But what about the others?” I said, still pacing. “There were eight other towns on the lease papers. We have to help all of them.” I turned to face Henry. “We have to go to those places and get there first. We have to warn them.”

Henry set down his pen and gave me a tired look.

“It’s nearly a thousand miles to Juneau. It’s the middle of October. I would need a dozen strong men to make that trip in midsummer.” He looked at the ground. “I’m sorry. It’s just not possible.”

Grandma came in before I had a chance to answer. I fussed at the problem silently while I helped Grandma set out breakfast. There had to be a way to stop him. If there really was oil up here, Mr. Glen was not the last wildcatter we would see.

Susi would know what to do. I wished I was still with her at the post office, and then it hit me. What could be simpler?

An hour later, when Uncle Jeremiah was getting the canoe ready for the trip up to Neah Bay and Henry was helping carry the boxes, I found Mr. Glen writing a letter.

“Are you going to take all the things we sold you along to Neah Bay, or will you send them back in the mail?”

“I’ll keep them with me,” Mr. Glen said. “Why do you ask?”

“When you go up north, you won’t find people living in a longhouse as we do. Almost everywhere people live in the government houses, and they’re very small.”

I looked at Henry for support and he said, “It’s true. Most tribes that have a longhouse don’t live in it anymore.”

“So there won’t be room for all your things in the little houses,” I added.

“I see,” said Mr. Glen.

“I could take them to Susi’s post office,” I said in a voice I hoped was not too eager. “I’m going there anyway. I promised Susi I’d bring her medicine plants.”

“It so happens I have a very important letter here,” Mr. Glen said. “To my patron. I need to draw funds to complete my trip.”

“I can have it in the mail for you this evening,” I said.

An hour later, I headed south with the letter safe and dry under my coat and the crate of rock samples strapped down in the bow. I felt like a warrior with prisoners in my canoe. I paddled hard and fast, turning out plans as I went. First, I would take all his rock samples and replace them with fakes, and then I would forge a new letter saying not to send money, that the trip was unsuccessful and no oil or gas could be found.

I paddled the whole way without resting and my arms were trembling when I landed on the beach at Kalaloch, but in my mind, I was already singing victory songs. I untied the crate and used the rope as a tumpline to carry the crate on my back. I trudged up the beach, resting once on a drift log, and then the rest of the way to the post office.

Susi was closing up for the day. Her smile behind the polished post-office counter was the best feeling of coming home I could remember. In that moment, I was positive everything would work out perfectly. I let the whole story of Mr. Glen’s visit gush out of me like water pours out of the mountains in spring, and her praise for my cleverness was better by far than the warmth of her fire and her good elk stew.

We were settled at the table upstairs when I got to the part about switching the rock samples so his partners would think he was not able to find oil. Susi got up and walked over to the window even though there was nothing but darkness to see. She let an uncomfortable silence follow my plan.

Finally, she turned to me and said quietly, “We must not do this. We will not.”

“What?”

“That man gave you a sealed letter and package to carry. He trusted you. This letter and box is the property of the person he sends it to. You will not open them.”

I couldn’t believe it—Susi, talking like a schoolmaster, like an Indian agent. “He stole from us,” I shot back. “And he means to steal more. He lied to us, claimed to be an art dealer when he’s nothing but a prospector.”

“You will not tamper with the mail.”

“Whose side are you on?” I shouted. “Just watch, he’ll take the oil, poison our waters, and leave us with nothing. If you stand by and let him rob from us and kill our salmon—our salmon, Susi! Who will protect them if we don’t? If you do this, you are no family of mine!”

Susi walked to where I sat and put her hand over mine on the table. Her hand was exactly the same as mine, down to the shape of each fingernail. A tear fell on the table beside our hands.

“You are my mirror,” Susi said. “When a white man comes to the post office and calls me squaw or spits on the floor in front of my feet, I look at your face and know that I am beautiful.” She paused, then her voice grew stronger like the grandmothers’. “I gave my word to defend the mail, defend it equally. Do not ask me to lie. Do not ask me to be one of them.”

Susi stayed there with her hand over mine and waited for me to speak, to look at her, but I couldn’t. She was right, and I hated it. I was right to stop Mr. Glen, and I knew it. I felt as trapped as I did in all those dreams where I heard my name called only to find a stone blocking my way.

“Raven tricked people,” I said at last. “He told lies, but he saved the people.”

Susi sniffed back her tears and said, “It’s true. What would Raven do?” She went to her cot and slid out the drum. She began to play, not a song, just tapping and listening, as if she were asking her drum a question.

I went to my coat and got out the diary from my pocket. I opened to a fresh page and drew my father’s Raven mask. I wrote down everything I remembered my father ever saying about Raven, not only the stories but what makes Raven think the way he does. I was four pages into it when I noticed Susi looking at me.

“What are you writing?” She came and sat beside me. “Can I look?”

No one had ever read my writing before. My face grew hot, and my heels drummed the floor as I watched her read.

“This is incredible,” she whispered.

I stared down at my feet. “The schoolmaster always said I had good penmanship.”

“It’s not the letters, Pearl, it’s the words. Clear. Simple. I can hear your papa’s voice when I read this. Hear him as if he’s in the room with us now.” She turned to me. “You must do this,” she said firmly. “You must do much more of this and show people.”

“But—”

“The people need this as much as they need good fish and warm houses.”

“But what if I’m wrong? What if I forgot some really important part?” I imagined the whole row of old women who sit in the honored position at all the feasts. I imagined them shaking their heads and clucking to each other about that pathetic Pearl Carver, a girl who didn’t know her own stories properly.

Susi put an arm around me. “The truth that you know is enough. If you put your words out in front of the people, they will give you more stories to tell. You just have to—”

“Have the courage of my ideas.” I let that thought echo in my head. I turned my diary back to the page with the whaler’s petroglyph, the page with the storyteller’s open mouth.

“Susi, do they have a post office at Neah Bay and Nitinat and Alert Bay?” I named all nine names on Mr. Glen’s list.

“Yes, of course,” she said.

“I know the words I have to start with.” I turned to a fresh page.

To all people who count the Pacific Shore their home and the salmon and cedars their kin:

A trickster is traveling among us. A small man who claims to be an art dealer. Do not be deceived by his money or his whiskey. I have learn

ed the truth.

That was the first of a thousand letters to tribes and governors and senators and presidents. Later, I became an editor of an Indian newspaper, and one of the authors of the Quinault and Makah dictionaries. I wrote a volume on medicinal plants and made sound recordings of the old songs. For seventy-five years, words pulled my life like a sail pulls a boat.

“Gram,” Ruby says, breaking into my thoughts. “I’ve been working on something, a surprise, and I want to show you.” She thumps her backpack to the ground by my feet and yanks open the zipper. She lifts my hand and silently sets a warm soft square in my palm.

I trace my fingers across the surface to see what she has given me. I don’t need my sight to tell it is woven work. Wool. The first few rows are loose and lumpy, but each one that follows becomes smoother, more confident. In the center, I feel a raised circle of wool. I gasp in wonder.

Ruby bounces from foot to foot beside me and then blurts out, “It’s Chilkat weaving, Gram, just like your mama used to do! Well, not just like, hers were bigger, obviously. But it’s the real thing with goat wool, thigh-spun yarn, and the warp is wound around cedar.”

I trace the circle again and again, and my heart drums with joy. It is my mother’s weaving exactly: the circle, the feel of the wool, the faint smell of the natural dye.

“How did you learn this?”

“From the Internet.”

“No way!”

“Way! I found this lady up in Alaska, and she found the last Chilkat weaver, and she learned from her before she died, and she makes the blankets now, and there’s a book and a website and everything.”

I shake my head in amazement. The one piece I had never been able to find in all my traveling and writing. All this time, there was a weaver, and I never found her. Suddenly, I miss my mother as I have not missed her in decades.

“I always wanted to learn, to teach you and your mom.”

“Oh,” Ruby says in a huffy voice. “So saving our language and testifying to save our fishing rights and serving on the tribal council for twenty years just aren’t enough for you? Jeez, Gram, don’t we have a tradition about being humble and grateful or something?”

Respect for seniors is not what it used to be.

“I wrote a grant for my school project,” Ruby went on. “Janine up at the museum helped me. I’m going to spend the summer in Alaska learning how to weave the way our ancestors did, and we’ll never lose the learning again.”

I smile, picturing Ruby in her saggy jeans and pierced nose concentrating on a loom for hours. Who would have thought my rebel, my drummer girl, would treasure the old ways so much?

“Thank you,” I say, and hold out my arms to hug her.

She steps in for only a second to kiss my cheek, and then shrugs it all off. “Really, Gram, it’s hip to be retro.”

“What is this on the back of your weaving?” I ask. My fingers tell me it is plain wool cloth and a flap held shut with a button.

“Oh, yeah.” Ruby goes back to her bouncing. “I got with the whaling commission, and they agreed you should be the one to bless the whale with eagle down. I know the pocket is supposed to be stitched to a full Chilkat robe, but honestly, Gram, it would take me two million years to finish a whole one. So I made this little piece into a pocket, and you can wear it around your neck.”

I shake my head. “You should wear this, not me.”

“But, Gram,” Ruby says, her voice raising a pitch higher, “I don’t know the blessing in Makah, not the whole thing by heart. You should say it. We couldn’t even have this whale hunt without you. You’re the girl who remembered.”

I take a deep breath and search for words to persuade her.

“You’re right. I will do the blessing. But you”—I reach a hand up to find her shoulder—“you should wear this weaving. You learned how to do it. You thought and worked and prayed over it. That gives you the right to wear it.”

I hear a little sniff and feel her nod her head. She bows in my direction and pulls off her baseball cap. I lift the woven pouch that holds the eagle down for blessing and place it around her neck. Already she is standing taller, like a princess.

“Walk with me, Ruby Carver, daughter of whalers.”

We make our way down to the beach and through the crowds that have gathered. I hear shouts and laughter and the click and whir of cameras.

“Auntie Pearl!” I hear the shout and heavy tread of Henry’s grandson, the one they call Tiny. He is so tall I feel like a kindergarten child beside him.

He throws a beefy bare arm around my shoulder. I smell sweat and seawater.

“Here’s your whale, Auntie,” he announces so everyone will hear. “Here is the whale you’ve been waiting for.”

He leans down and whispers, “It went exactly the way you said it would. Our whale rose her head up to look at us, and then she rose again. And I knew. It felt exactly right.”

He pauses and draws in a breath. “Like the thing I’ve been waiting my whole life for and didn’t know it until now. Come look, Auntie Pearl,” he says, taking my hand. “She’s beautiful.”

I walk forward through the crowd. The whale’s shadow falls over my shoulders. I remember the copper-green shine of the whale on the petroglyph at the seal hunter’s beach. I reach out my hands and press them to the whale’s skin. I feel warmth and life press back.

Author’s Note

A cedar does not have one taproot but rather relies on a multitude of broad and shallow roots that intertwine with the roots of other cedars to remain upright, not as a single tree but as a grove, an interconnected forest. Stories grow in this way. There is no single origin for this book but a weave of threads that has brought me full circle more than once in my life.

CONNECTIONS

As a fifth grader, I saw the Raven stories told and danced by Chief Lelooska and his family at their longhouse in Ariel, Washington. When the dancer pulled the hidden string that split the mask open to reveal the sun, it seemed as magical to me in the firelight as any movie special effect. I never dreamed I would grow up to be a teacher on a reservation where similar Raven stories were told. Yet only a dozen years later I was on my way to Taholah to interview for my first teaching job. The sight of the Quinault River flowing into the ocean captivated me as no other landscape had before. The Olympic Peninsula has some of the best-preserved stretches of wilderness beach and temperate rain forest in the United States. It is a unique and stunning ecosystem, receiving fifteen feet of rain a year and nurturing trees that can live more than a thousand years. I was equally captivated by everything I learned about the local culture from my students and neighbors. Their enthusiasm for traditional stories, music, and dancing made me curious about my own history, including Irish ancestors who, like the Quinaults, fished for salmon and struggled to keep their own language and culture alive.

During our daily read-aloud time, my fifth graders once asked me, “Why is the story never about us?” launching a long conversation about why having not just generic Indian stories but a story that was about the real life of their own tribe was so important. We talked about how books are made and who makes them. In the end, Ilene Terry, who often summed things up for her classmates, said, “I guess nothing is going to change unless somebody here grows up and writes that book.” I did not imagine I would be the one to grow up and write the book, but here I am, full circle again. Now Ilene is the teacher at Taholah Elementary, where most of my former fifth graders are the parents of current students.

CULTURE AND RESPECT

Many years of research and hundreds of revisions went into the making of this book. Historical fiction can never be taken lightly, and stories involving Native Americans are particularly delicate, as the author, whether Native or not, must walk the line between illuminating the life of the characters as fully as possible and withholding cultural information not intended for the public or specific stories that are the property of an individual, family, or tribe. With help from the historians, curators, fish

ermen, artists, and carvers I’ve spoken with over the years, and in particular with the help of Kathy Kowoosh Law, a Quinault and Makah historian, and Veronica “Mice” James, the Quinault language and culture teacher, I’ve attempted to walk this line with care and respect.

For example, there are secret rituals involved in whale hunting that belong solely to members of a whaling family. With a girl as my narrator, I was able to describe the whale hunt from the perspective of someone who, because of her age and gender, was an outsider to that information, leaving the preparatory rituals a mystery, as they should be. Many characters from the local mythology are referenced in the story. One of the most striking things to me about my time among the Quinault was the legacy of story characters that lived so vividly in the minds of my students. None of them ventured out in the dark, swam in the ocean, or wandered alone into the forest. They could describe in lurid detail what would befall them if they dared. I know many of these stories, but they are not mine to tell. I have alluded to the Pitch Woman and the Timber Giant and a few others, trusting the reader to conjure their own frightening scenarios and leaving the full telling of these stories to the people who have a right to share them.

I have referred to the Nuu-chah-nulth as Nootka in this book. They live on the west coast of Vancouver Island and are closely related in language and economy to the Makah. They were called the Nootka in the 1920s, and I have used the name here for authenticity. Throughout the book I have chosen names and spellings of the era as nearly as I can determine them, recognizing that often there are multiple names and spellings for a town or tribe and that some names are now considered incorrect.

WHALING

Ozette, the site of Pearl’s story, is a former village site of the Makah. It was occupied by whaling families from prehistoric times to the 1930s, when it was abandoned for its lack of proximity to a school. It is also the site of an important archaeological dig, which provided many of the artifacts housed at the Makah Cultural and Research Center in Neah Bay. A visit to the museum with my students brought me to the question that launched this story. For the Makah, whaling is not a job. For generations, it was the lifeblood of their economy and the cornerstone of their spiritual and cultural life. The Makah voluntarily gave it up in the 1920s. I was haunted by the notion of what that would mean, not on a broad scale but at the level of one family’s everyday needs. Subsequent visits and conversations with staff have been key to my understanding of what whaling meant and continues to mean to the Makah. The frame of the story, with Pearl as an old woman witnessing the resumption of the whale hunt, is based on the historic day in May 1999 when the Makah successfully completed their first traditional whale hunt in seventy years. In this way, Pearl is a tribute to Native grandparents everywhere who work to keep cultural memory alive.

The Turn of the Tide

The Turn of the Tide Heart of a Shepherd

Heart of a Shepherd Second Fiddle

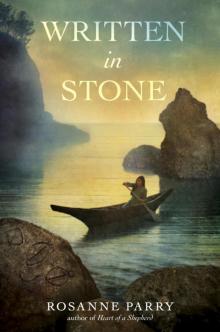

Second Fiddle Written in Stone

Written in Stone