- Home

- Rosanne Parry

Heart of a Shepherd

Heart of a Shepherd Read online

For Bill, who came home

JULY

The Chess Men

AUGUST

Cow Camp

OCTOBER

First Flock

DECEMBER

The Man of the House

FEBRUARY

Serving the Altar

APRIL

Promises Made

MAY

Boots on the Ground

JUNE

The Veterans

AUGUST

Waiting for Beautiful

AUGUST

Coming Home

JULY

Grandpa frowns when he plays chess, like he does when he prays. He's got a floppy mustache that pulls that frown right down past his chin. He used to have freckles like me, but I guess they expanded on him because his whole face is pack-mule tan, with a fan of wrinkles at the corners. Years and years of moving cattle and mending fences gives a man a fearsome look, and I bet if I work at it, I can look just like my grandpa by the time I go to board at the high school. But the fences are mended for now and the cows are up in the mountains with my older brothers, so Grandpa and me are playing chess out on the back porch.

Grandpa's chessmen are world-famous around here. They came over the Oregon Trail with Grandpa's grandfather in the covered wagon, and before that they came straight from Paris, France. They were carved by hand from ebony for the dark side and ivory for the light. The pawns all have round helmets and longbows. Everyone else has a sword, even the bishops, and their faces are dead serious, which is what you want when there's a war on.

Grandpa is the chess champ of Malheur County, Oregon. We've been playing each other for years, so I've got him pretty well sized up. He always opens by moving the middle pawn up two spaces. But after that first move, he's as wily as a badger and twice as tough. I haven't beaten him yet, but when I do, it will be worth a town parade.

Now, to my mind, pawns are a shifty-looking bunch, plus they clutter up the board, so I try to clear most of them off right away, his and mine. I like my knights to have plenty of room to ride. My queen's knight rides a paint mustang. That horse has got a temper; she's lean and fast, and brave as a lion. My king's knight rides a Clydesdale; not so much speed, but plenty of power.

Rosita's my queen, of course. She's a fifth grader up at the school, and my best friend's sister. She can birth a lamb and kill a rattlesnake with a slingshot, which is what I look for in a queen. Plus, she's as pretty as a day in spring, and she laughs when I'm the one talking.

I bet Grandpa's working on putting me in a fork. That's his favorite move, but I see it coming a mile away, so I take a sip from a sweaty glass of lemonade and talk things over with the men. My king's bishop is all for killing Grandpa's queen before she can get us, because, after all, he is an excellent swordsman. The trouble is, Grandpa's queen would have to be Grandma, and I couldn't let anything bad happen to her, now could I? It's confession for sure, for killing your grandma.

My queen's bishop and I talk the other bishop out of it, which we do a lot. The queen's bishop is the more reflective type because his hands are carved together for praying.

Grandpa leans forward in his straight-backed chair, still frowning. Dad's orders sit on the card table beside the chessboard, in a tan army envelope. I made Dad show me, because I couldn't believe what he said. They're going to send him and the entire 87th Transportation Battalion all the way to Iraq. Reserve guys are only supposed to go places for two weeks—maybe three, if there's a hurricane in Texas. Fourteen months! It says Dad will be gone fourteen months, right in print. Like this is going to sound better to me than Dad is going to miss my birthday two years in a row.

Grandma's got him in the kitchen. I can hear the buzz of the clippers through the screen door. She takes about two minutes to cut my hair, but she's been at it with Dad for half an hour. I think she just wants an excuse to rub some extra blessings into his head. I hope she keeps him in there for an hour. He's going to need all the blessings he can get in Baghdad.

Grandpa pauses so long in the game, I get to wondering if he's even playing. He's been writing letters to our senator to oppose the war ever since it started. Half the Quaker congregations west of the Mississippi have signed them. Grandpa is not an out-loud worrier like Grandma. He just spends more time in the evening praying and writing in his journal.

“He doesn't really have to go, does he?”

Grandpa looks up from the board, straight at me.

“He took a vow when he put on that uniform. A promise is a binding thing, Brother, before the law and before God, too.”

“God doesn't believe in war, does he? You don't.”

“Protest is my calling. Your dad's is to take care of the men in his command. He can be faithful in that.”

The sun is just starting to go orange, and the wind settles down like it does this time of day. The whole ranch gets quiet, like it's waiting for the next move. Grandpa scoots his bishop up three spaces. He looks at me and smiles.

A fork! I knew it. My queen's in danger! Her knight is on the other end of the fork. What'll I do?

The queen's bishop starts right in on his rosary and my two remaining pawns fit an arrow to the bow, but King Grandpa doesn't flinch.

My king's bishop is a string of bad advice, and my king's knight says, “It's a rough spot, laddie, but one or the other of them will have to go. You know it's true.”

Both horses nod solemnly in agreement.

“But, Your Highness,” says the queen's knight, “there's a way out, Your Majesty. I could ride up behind King Grandpa, and he wouldn't see me. Just let me take two turns. Come on.”

I see what he's driving at, except it still wouldn't save my queen. Knights are brave enough in a battle, but they're not too bright, which you can tell by the way their eyebrows are all carved into one straight line.

“Think it over, Brother. Don't rush into anything,” Grandpa says, which is what a man usually says when he'd like you to get on with it. But Grandpa's good at waiting, for a grown-up. He leans an elbow on the porch rail and stares out at the bluff where we've been finding cougar tracks all month long.

My queen just looks at me with those serious brown eyes and the long curly black hair. She likes me, I know she does. And what's better, she's trusting me to do the right thing. I stroke her hair with my finger just once, so she knows I like her too, and then I slide my king up one space, right between Rosita and her attacker.

“You can't move into check,” Grandpa says.

“Yes, sir,” I say, sitting tall on my barrel and slapping dust out of my jeans. “If you want me off this square, you're going to have to fight me.”

“Well done, sir! Oh, bravely done!” shout my knights.

My king's bishop bows his head. “Your sacrifice will be remembered for all eternity. “

The queen's bishop starts warming up the last rites.

The dead pawns at my feet send up a cheer, but I can hardly hear them because she smiled at me! A little wooden smile as tender as a snowflake on my eyelashes. I'm so proud I could bust. Grandpa looks from me to my queen, and back at me again. He smiles a little.

“Are you sure you want to play it this way Brother?”

“Yup.” Is he kidding? I never get to be the hero.

“Checkmate.”

I did it! The game's over, and my queen is still standing!

Grandpa just shakes his head, but I can't stop smiling. Dad wanders over, brushing haircut stubble off his shirt. He gives my shoulder a squeeze.

“Fourteen months is a long time. We should talk,” Dad says.

Grandpa gets up, straps on his tool belt, and heads up to the barn to fix the lamb pen. I can hear Grandma moving the pots and pans around in the kitchen and

whistling some old Irish tune. Dad looks out at his land. Red Rock Creek comes down from the reservoir, a mile to the north, and flat green pasture stretches across the canyon floor to the dry hills on either side. There's a stand of willows by the water, and one giant cottonwood shades the south end of the barn and holds up my tire swing.

“Did you beat your grandpa at chess yet?” Dad says.

“Not exactly.”

“Never mind, Brother. I think I was about fifteen before I won my first game.”

Everybody calls me Brother because I've got four big brothers. My real name is Ignatius. Guess they ran out of all the good saints by the time they got to me. Lots of things ran out by the time they got to me. My brother Frank says it could be worse—they could have picked Augustine or Cyril—but honest, I wouldn't have minded being Gus, or even Cy But Ignatius pretty much shortens to “Ig” or “Natius.” That's not even a good name for a cow. Heck, I wouldn't name a pig either one.

“So what do you think?” Dad says, nodding in the direction of the envelope with his orders.

“I can't believe it. You've been in the reserves forever, and they've never asked you to do anything like this. Jeez, Grandma was in the reserves for thirty years, and they never sent her to a war.”

People are going to be talking about this all over the county. There's a list of a hundred names in Dad's command. How's he going to tell all those families their dads are going to leave? Every volunteer fireman in a hundred miles is on that list. Our postmaster; the school janitor; the basketball coach; Arnie, who owns the only gas station in town; and every member of the school board is on that list. A month from now, they'll all be on a plane.

I line the chessmen up in their box and sit on the porch rail next to Dad. I rub his bristle-short hair. He used to have red hair like mine, but what's left after Grandma's clippers is mostly gray fuzz. Dad looks up at the hills. He's standing more like a soldier already.

“What if your men don't want to go?”

“It's our mission, and we'll see it done.”

Dad says it flat and cold, like a person isn't even allowed to think about not going. The chickens begin their nightly parade up from the banks of the creek behind the house to the chicken shed next to the barn out front.

“Paco and Rosita's mom and dad are on that list. It's not fair they both have to go. Rosita's too little to have her mom gone.”

Truth is, every other kid in Dad's battalion has a mom at home, everyone except me. I've got an artist mom who lives in Rome, Italy. She might be famous— it's hard to tell from her letters—but she's definitely not at home.

Dad looks at me and shakes his head. “Rosita's only a year younger than you. Your friends have got plenty of aunts and uncles. They've got a plan for this.” He turns back to studying the land, and after a while he says, “Everyone has a plan for this.”

Usually, when I look out the back porch, I see willows hanging over the creek and red-tail hawks riding the thermals. Today, I see the pasture gate that needs a new hinge, and the south side of the barn that needs paint, and the hayfield that needs mowing, and the tractor that needs a timing belt.

Does he really have a plan for this, the cows and the sheep and the land and me?

I straighten up and measure myself against his shoulder. I've got a ways to go, but my boot's almost as long as his, now that I got a new pair, and I can wear the same work gloves he does. I might be skinny, but I'm big enough to run the tractor and the loader. Lambing and calving? It's bloody, but I know how to do that, too.

“I'm going to take care of this place,” I tell him. “It's going to be here. It's going to be just the way you remember it when you get back.”

That's my mission, and I'll see it done.

AUGUST

The trouble with four-thirty in the morning at our cow camp up in the mountains is not just that it's darn early, it's freezing cold too, even in August. I just want to hide in the bottom of my sleeping bag, but I know better than to make Dad call me twice. I slide down from the top bunk and gasp in a big, chilly breath when my bare feet hit the cabin floor.

John's awake already, and sitting on Pete's empty bunk. He looks an inch taller to me since he got back from basic training in June. Maybe it's just the extra muscles. Now that they both have army haircuts, Jim and John could be twins. They both have Grandpa's nose and Dad's square chin, and we all have Grandma's blue eyes. Frank's still got a mop of red hair. It's all I can see sticking out of the top of his sleeping bag. Jim pokes him a couple times to get him out of bed, and Frank growls at him in a much deeper voice than he used to have.

I shiver into my jeans, boots, and three layers of shirt, and head outside. Dad's standing by the gas lamp on the picnic table, with a towel, a razor, and an empty bowl. There's a sheet of ice on top of the water jug.

“I guess we'll have to wait and shave at home,” Dad says.

“I'm not shaving,” I mumble, unlatching the food box and rooting around for breakfast. I'm never going to shave, if I can help it. Dad decided Frank's big enough to do it this summer because he's going off to high school in a couple weeks. Between the freezing-cold water and the slightly rusty razors, I thought old Frank was going to bleed to death each and every morning.

Dad gathers an armload of wood from the woodpile next to the horse shed and heads back inside. I balance eggs, steak, and coffee beans in one hand and relatch the box with the other. There's nothing grosser than a raccoon eating half your food and pooping on the other half, so I never forget to lock up the box.

Back in the cabin, Frank is finally up and dressed. Dad fusses with the woodstove and then slides the cast-iron skillet into place. I pull up a stool to the long table in the middle of the room, put a couple handfuls of beans into the coffee grinder, and start cranking. John clears away the cards and poker chips from last night and sets the table. Jim is the oldest brother here, so he heads out to the shed to take care of the horses.

I keep thinking one of my brothers is going to say something about Dad leaving today, but I guess not talking is a big tradition nobody told me about up here at cow camp. I've been dying to come every summer since I was nine, when Frank went with the big boys and left me the only kid at home with Grandma. You have to be twelve to go; that's the rule. Dad made an exception this year. I'll be twelve in October, and Dad won't even be back home next summer.

The first orange-pink light from the east window warms up one end of the table. Frank blows out the lamp. Dad puts the last of his Arabic CDs into the player and pops on the headphones while he cooks breakfast. He repeats the same phrases over and over, switching from Arabic to English and back again.

“How many kilometers to the well? The hospital? The police station? The nearest road?”

He turns the steaks over and cracks an egg next to each one.

“Do you need medical help? A translator? Please remain calm. Please clear the area.”

He puts two shakes of salt and pepper on each egg and turns it over.

His voice sounds so strange to me in Arabic. His words are stiff and formal, and when I hear them, I feel like he's gone already.

As soon as the steak and eggs smell done, the rest of the brothers are at the table like a shot. I don't even have to call them. Somebody should say something about Dad going. He and I are going to ride back home this morning and then drive to the airport this evening to send off his unit. Fourteen hours and he'll be in the air. But the brothers just pull up their chairs, speed through table grace, and start eating like today is the same as every other day.

Dad's no help either. He goes over the plan of the day with Jim. They drone on about where to move the cows for the best pasture. John and Frank just nod along with the rhythm of Dad's voice as he goes through the list of things to be careful about.

When I was little and my brothers got to bragging about cow camp, they always talked about the jokes they played on each other and the singing at night and the time the bishop came up to bless our cattle. This ye

ar it's different. Frank did play a couple jokes on me, but nobody laughed much, and we didn't sing at night, not once. Dad played his harmonica a little bit, but most evenings we sat looking at the fire or playing cards while Dad listened to his language tapes or made up lists and plans.

“Ready to ride home, Brother?”

Dad breaks into my thoughts. I nod, take a last gulp of coffee, and dump my dishes in the dishpan. The brothers head out the door. Dad washes up the plates and pots. I stuff the last of my dirty clothes, three paperbacks, and a book light into my school backpack and head outside.

Jim is under the cluster of mountain larch by the horse shed. He has already got Dad's horse, Ike, saddled. Ike's tall for a quarter horse, and he's probably got some Kiger mustang in him, because he's got a dark stripe down his back and an attitude. He's as good a working horse as we've ever had on the ranch, but he doesn't think much of me.

Spud's my horse. She's just a Shetland pony. I've been riding her since I was four. I'll probably be too tall to ride her next year. Still, I'm glad she's with me now. She might not be fast, but she's plenty strong, and she'd never let me fall. I stroke her head while Jim tightens the saddle girth. She doesn't like that part. When it's done, she nudges me on the shoulder and gives me horse kisses on my neck.

“Listen, Brother,” Jim says, throwing an arm over my shoulder and steering me toward the clearing in front of the cabin. “Grandma's going to need lots of extra hugs, with Dad gone. You take good care of her.”

Must be an oldest-brother thing to say, because Pete said exactly the same thing to me three weeks ago when his leave was up and he went back to his platoon at Fort Hood.

“I want you to call me right away if something happens,” Jim goes on.

I nod.

“Call me even if I'm in class. Boise's not that far away. I could be home in an hour and a half.”

“But Dad said no cutting class to do ranch work. Jeez, he said it like a hundred times, remember? The hired man is supposed to do Dad's work.”

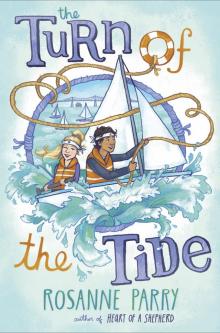

The Turn of the Tide

The Turn of the Tide Heart of a Shepherd

Heart of a Shepherd Second Fiddle

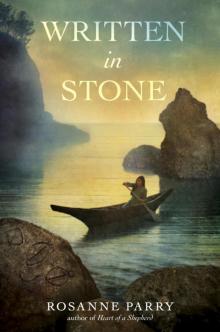

Second Fiddle Written in Stone

Written in Stone